About the Author and Consultants

David Balog, a freelance science/medical writer, served as an editor at the Charles A. Dana Foundation from 1995-2006. There he worked for William Safire, Language Columnist for the New York Times. David created, wrote, and edited The Dana Sourcebook of Brain Science through four editions. More than 50,000 copies were distributed to elementary schools, middle schools, colleges and to professionals and the general public. He worked with leading brain scientists and doctors, including Nobel laureates. David Balog has created the Healing the Brain series of books and videos. Please visit HealingTheBrainBooks.Com to learn more. David is a graduate of Hamilton College, where he received a BA in History. He has a lifelong interest in politics and government.

Gerry Huerth has a BA degree in English, an Associates Degree in Nursing and a Masters degree in Human Development. He was an early member of FREE, the first Gay and Lesbian College Organization in the United States, 50 years ago. Gerry also served on the board of directors of Hospice of Maine (an early hospice). He also volunteered for The Farm Workers Union in California and started a personal care service company for mentally ill people in Minnesota. Most recently he taught First Year Experience and Community Organizing courses at North Hennepin

Community College in Minneapolis. He continues to co-lead workshops about sustainability, non-violent communication, and historical trauma. He is currently on the board of directors of Off the Blue Couch, a not-for-profit organization that works to empower marginalized people.

Jessica Smith-Jones is a career assistant to political candidates and politicians in New York City. She also has been an entrepreneur, starting and managing her own business services company. Jessica has devoted her time to the African-American community and to organizations supporting former foster children.

Impeachment 101

Wikimedia.com

Donald Trump, 45th president

of the United States.

Donald Trump has joined the company of a small group of presidents now that he is the subject of an official impeachment inquiry in the United States House of Representatives. Only three previous presidents experienced the impeachment process: Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton, who were found not guilty after trials in the Senate, and Richard Nixon, who resigned to avoid being impeached in the House and removed from office by the United States Senate.

Contrary to common knowledge, impeachment does not mean automatic removal from office. It is a much more complicated, considered process. Rarely used due to its irrevocable nature, impeachment, as defined in the U.S. Constitution, was a critical feature of the government created by the Founding Fathers. The new nation had just freed itself from rule by a tyrannical monarch and wanted nothing remotely similar in its newly created government.

Impeachment was considered extensively in The Federalist Papers, a collection of essays written in 1788 by John Jay, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton. These articles urged citizens of New York State to ratify the United States Constitution. They promoted the ideas and plans that had been debated and drafted at the Constitutional Convention the year before. The Federalist Papers is considered one of the most significant American contributions to political discourse and az definitive source for understanding the original intent of the framers of the Constitution.

From the Federalist Papers, written by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay.

In Federalist 51, James Madison argued for a watchdog system between the three branches of government: the legislative, executive, and judicial. Federalist 51 was entitled “The Structure of the Government Must Furnish the Proper Checks and Balances Between the Different Departments.” Madison, a future president, wrote that “If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.”

Wikimedia.com James Madison, “If angels were to govern men...

Wikimedia.com James Madison, “If angels were to govern men...

The most practical way to keep the government in check, Madison argued, was to structure it so that politicians must compete with each other. “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition,” he wrote. During the Constitutional Convention, Madison also said about impeachment: “You need it because a president might betray his trust to foreign powers."

Having said that, the Founders did not invent impeachment. The concept had its roots in British common law, and was used beginning in the 14th century. The House of Commons served as prosecutor and the House of Lords as judge in an impeachment proceeding against a government official charged with a criminal offense. Conviction on impeachment could result in fines, imprisonment, and even execution. In the United States, the penalties extend no further than removal and disqualification from office. Possible criminal liabilities, however, remain for an impeached and removed official.

In the early 1800s, an understanding that cabinet ministers were responsible to Parliament (rather than to the monarch) ended the use of impeachment in Great Britain.

In the United States impeachment has rarely been used, largely because it is so potentially overwhelming to the political system. Impeachment can occupy Congress for a long period of time, involve substantial amounts of testimony, and bring about deep political conflict.

Attempts to amend the procedure, however, have not worked, partly because impeachment is regarded as a key part of the system of checks and balances in the U.S. government. These rules describe the intricate inter-relatedness of the three branches of government and their powers to hold each other accountable.

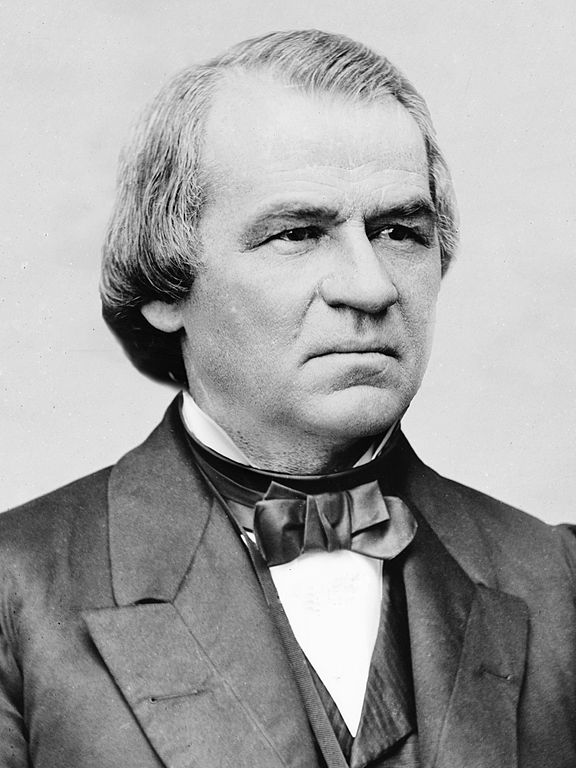

Wikimedia.com Andrew Johnson, 17th president of the United States.

Wikimedia.com Andrew Johnson, 17th president of the United States.

The idea of impeaching and removing a president is the ultimate accountability of high officials to the land they swear a high oath to defend. The actual language on impeachment in the Constitution says that the president, vice-president and all civil officers of the United States "shall be removed from office on impeachment for conviction of treason, robbery or other high crimes and misdemeanors,” terms debated by politicians and historians to this day.

Order on Amazon or Kindle!

Congressman Gerald Ford, who became president as the result of an impeachment process, notably said that “an impeachable offense is whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers it to be at a given moment in history.” High crimes and misdemeanors can include obstruction of justice or perjury (lying under oath during a trial or investigation), violating an oath of office, or flouting the emoluments clause of the Constitution. This stricture prohibits members of the government from receiving gifts, offices, or titles from foreign states and monarchies without the consent of the United States Congress.

Previous impeachment proceedings: 2 acquittals, 1 resignation

The nation's experience with presidential impeachment begins with Andrew Johnson, the 17th president, who assumed office after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in 1865. During the Civil War, Johnson was the only Southern senator to remain loyal to the Union and Lincoln chose him as vice president for his second term. Six weeks after Johnson became vice president, Lincoln was assassinated. As president, Johnson took a moderate approach to restoring the South to the Union, and clashed with congressional Radical Republicans who wanted to ensure congressional rather than presidential control Reconstruction. Congress passed a number of measures to protect Southern blacks over Johnson’s veto. Johnson wanted to quickly restore the Southern states to the Union. He granted amnesty to most former Confederates and allowed the rebel states to elect new governments. These

Wikimedia.com Ticket to Senate Impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson.

Wikimedia.com Ticket to Senate Impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson.

governments, which often included ex-Confederate officials, soon enacted black codes, measures designed to repress the recently freed slave population. The Radical Republicans viewed Johnson's approach to Reconstruction as too lenient toward the former Confederacy. Hostilities between the president and Congress mounted and in February 1868, the House voted to impeach Johnson. Among the 11 charges, he was accused of violating the Tenure of Office Act by firing the Secretary of War, who opposed Johnson’s Reconstruction policies. At his Senate trial, Johnson was acquitted by one vote.

Richard Nixon, the 37th president, was elected in 1968 and reelected by a landslide in 1972. He was embroiled in controversy throughout his time in office. During his term, the Vietnam War continued to stir public unrest. A burglary at the Democratic National Committee

Wikimedia.com Richard Nixon, 37th president of the United States.

Wikimedia.com Richard Nixon, 37th president of the United States.

was called Watergate (after the location of the Democratic headquarters).

Investigations beginning in June 1972 eventually revealed a widespread covert, illegal political operation run by the Nixon White House. A deep political and constitutional fight ensued.

In Nixon's case, first Senate hearings and then a Congressional impeachment inquiry deepened the crisis in 1973 and 1974. Nixon’s popularity plunged. When he was revealed on tape to have lied about his early knowledge of the burglary and cover up, Nixon’s fate was sealed. Republican leaders went to the White House to tell Nixon that he could not avoid removal from office. He resigned even before the House had voted on a formal impeachment charge.

President Bill Clinton was impeached for obstruction of justice and perjury. The 42nd president of the United States from 1993-2001,

Wikimedia.com

Wikimedia.com

Bill Clinton, 42nd president of the United States.

Clinton faced an impeachment that was generally considered a partisan type of vote. Only Republicans in the House voted affirmatively. In December 1998, Clinton was formally impeached by the House for perjury and obstruction of justice. The charges related to his testimony denying a sexual relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky, testimony given during a deposition for a sexual harassment lawsuit filed by another woman, Paula Jones. In the Senate trial, the perjury charge received forty-five votes, and the obstruction of justice charge received fifty votes, both falling well short of the two-thirds threshold for removal.

9 essential facts to know about impeachment

There is a step-by-step process for impeaching a president of the United States. It all centers around Article I Sections 2 and 3 of the Constitution and around rules of conduct set by the House of Representatives and the Senate.

One. The House Judiciary Committee is specifically charged by the Constitution to begin the process. When a majority of the committee members vote in favor of what’s called an “inquiry of impeachment” resolution, the process begins.

Two. That initial resolution goes to the full House of Representatives, where a majority has to vote yes, and

Wikimedia.com

The United States Senate in session.

then votes to authorize and fund a full investigation by the

Judiciary Committee to determine if sufficient grounds exist for impeachment.

Three. The House Judiciary Committee begins hearings. Its investigation can rely on investigations undertaken previously by the FBI, the Justice Department or a Special Prosecutor.

Four. If a majority of the Judiciary Committee members decides there are sufficient grounds for impeachment, the committee issues a resolution describing specific allegations of misconduct in one or more articles of impeachment.

Five. The entire House then debates that Resolution and votes–on all articles or on each article separately. The House isn’t bound by the Committee’s work. It may vote to impeach even if the Committee doesn’t recommend impeachment.

Six. If recommending impeachment, Congress then notifies the Senate, which has longstanding rules and procedures for conducting a trial. The House’s formal Resolution of Impeachment becomes in effect the charges for a Senate trial.

Seven. The Senate presents a summons to the president, who is now effectively the defendant, informing him of the charges and the date by which he has to respond.

Eight. The Senate conducts its trial. In that trial, those who are representing the House--that is, the prosecution--and lawyers for the president, both make opening arguments. The case proceeds as a regular court trial, with evidence, witnesses, examination and cross-examination. Uniquely, the trial is presided over by the chief justice of the Supreme Court.

Wikimedia.com

The Senate held hearings on the Watergate investigation in 1973.

The House managers and counsel for the president then make closing arguments.

Nine. The Senate meets, first in closed session to deliberate, just as a regular jury does.

The Senate then returns in open session to vote on whether to convict the president on the articles of impeachment. Conviction again requires a super majority--not 50 percent but two-thirds of the Senate.

Conviction on just one article of impeachment results in removal from office. Such a conviction also disqualifies the now former president from holding any other public office. Conviction still leaves a former president liable to future legal proceedings and punishment.

In a notable and disputed exception, President Ford granted a full pardon to his predecessor, Richard Nixon, shortly after his resignation, for any possible criminal acts he may have committed in office.

Quotes on Impeachment

“The awful discretion, which a court of impeachment must necessarily have, to doom to honor or to infamy, the most confidential and the most distinguished characters of the community, forbids the commitment of the trust to a small number of persons.”

- George McGovern, former U.S. Senator and presidential candidate.

“When people ask if the United States can afford to place on trial the president, if the system can stand impeachment, my answer is, 'Can we stand anything else?'”

“The Democrats had long labeled the impeachment debate a distraction from the urgent business of a great nation. But the Republicans argued that the pursuit of justice is the business of a great nation. In winning this point, they caught the falling flag, producing a triumph for the rule of law, a reassertion of the belief that no man is above it, and a rebuke for an arrogance that had grown imperial.”

- Alexis de Tocqueville, author, Democracy in America

“There are many men of principle in both parties in America, but there is no party of principle.”

All photos this section courtesy Wikimedia.com.

Learn more about it.

Khan Academy

Library of Congress

White House

Also available online from the author:

A primer, in 30 pages, on the American government, its surprising history, strength--and fragility. Includes the 9 reasons why 100 million Americans who don’t vote, should.

The Supreme Court makes decisions that have deep lasting effects on American life. Americans generally don't realize that their vote for president, who nominates new justices, essentially governs the entire process. This guide demonstrates key court decisions that

have shaped America.

Visit www.commongroundbooks.org

Healing the Brain Series

Available online and at

Healing the Brain:

Stress, Trauma and Development

Praise for the series:

“David Balog understands the strain of alienation, so he tackles this subject with compassion and concern. Mr. Balog draws on his knowledge of brain science to give readers insight into what

happens to young people under tremendous stress….”--Gary L. Cottle, author

“Easy to read. Difficult to put down.”--Micheal J. Colucciello, Jr., NY State pharmaceutical researcher, retired.

“Well researched, fleshed out with relevant case histories, this book packs a lot of solid information into its 172 pages. Written in an engaging style for the layman, it covers a wide range of topics. One learns a great deal about the biology of stress, particularly the vulnerability of the brain in the pre-adult years. This book also provides a glossary of key brain science terms and a listing of community organizations and resources on the brain.”--Gary Bordzuk, Librarian, Oceanside, NY

Healing the Brain:

Alcohol and Drugs

Healing the Brain:

Stress, Trauma and LGBT Youth

Visit www.HealingTheBrainBooks.Com